Stories & More

Short stories

Travel

For writers

Miscellany

Kenora & Jake Stories

by Hyacinthe Miller

•

30 January 2026

The first 'who am I' defining moment that I remember occurred in grade four, when Sandy Padano took a swing at my head with her Sunshine Family mom doll in the junior girl’s washroom. Sandy – whose dad was Spanish and had a complexion as dark as mine - screamed “spot-face, spot-face, you’re a dirty brownie, you’re a dirty brownie” until the gym teacher dragged her away and stashed her in the first aid room for a time out. I knew what I looked like – sort of what you get in a cup of cocoa mixed with cream – half of my mom’s colouring, with a sprinkling of freckles, and half of my dad’s, with lots of curly hair thrown in. Sandy knew she was in trouble, but it was me who barricaded herself in the girl's bathroom. I cried so hard I was at the gasping, damp-faced stage where I didn't care what happened next. No one had ever called me names before, but I knew it was wrong. I had no idea why, to Sandy, I was somehow less than what I had been the day before. That made my stomach hurt. They’d had to interrupt the janitor’s smoke break so he could unscrew the hinges from the bathroom stall door. I remember he smelled of stale beer and all-purpose cleaner. My homeroom teacher finally coaxed me from my perch crouched on the toilet seat. The principal had whispered that Sandy ‘had issues’, but at nine, what the hell did that mean to me? For the rest of the afternoon, I was a mini-celebrity because my class got a spare while the teacher dealt with the parental aftermath with Sandy's harried mother. For a couple of days afterwards, though, the side-eye looks and grimaces from my classmates re-opened the word-wounds. After some brief commiseration, my parents told me to stop sulking and grow a thicker skin. My brothers sometimes looked at me like I was from somewhere else. They were younger, and being boys, just didn't understand what it meant to be me. At the start of grade five, I got better at pretending to be oblivious to the hurts flung by folks I downgraded to unimportant or stupid. I convinced myself that I liked being ‘different’, and saved my tears for the darkness of my bedroom. On a more positive note, Sandy’s spittle-fuelled tirade fueled my determination to be the best at everything I could – school work, crafts, sports. What that got me was more names like ‘browner’ and ‘keener’. "No one promised you a rose garden," my mother said one day as I was wallowing in my latest drama. I’ve always been skittish about how other people saw me, what they thought of me, how I sounded when I spoke. I wanted to be the 'good girl', the 'smart girl' who could be counted on to help out an adult. Hence my transformation was to focus on what my teachers thought, rather than care about my classmates. But that came at a cost, because it was hard to keep track of which face I was wearing on a particular day. I didn’t keep many friends for long, because I enjoyed winning too much, and I hadn't learned that letting someone else come out on top was a positive thing to do for maintaining relationships. I became what my dad called a ‘shapeshifting pleaser’, except when I deployed competitiveness and a smart mouth as a force field. Let’s just say I haven’t always been well defended. Which is a roundabout story about how the ‘me’ – Kenora Tedesco – began to be shaped by events I couldn’t control. In grade six, I had stopped believing in the Easter Bunny and the Tooth Fairy. My younger brothers still bought the hype our parents dished out, but I refused to look under my pillow for cash when I lost a tooth, or write to Santa asking for stuff that I'd find on the top shelf of my parents' walk-in closet. I had no interest in a Lite-Bright or a can of Silly String, although if I could have wheedled an old book of magic spells, a short-wave radio setup or a $500 gift card for books out of mom and dad, I might have written out the best begging letter ever, on toilet paper. Without me asking, though, my parents gifted me a Magic 8 Ball when I was ten. All I wanted to know was if Jimmy Tudhope, the star hockey player in grade seven liked me. The answer was, ‘Outlook hazy’, which in retrospect made sense, because he was in a different orbit than me. I should have been more curious and asked what would happen to me at 20, 30 and onwards. Why? Because the older I got, the more I took refuge in working harder at being the best I could be, even after that became a catchy recruiting slogan. Did my life turn out peachy-keen better? Better than Sandy’s. A couple years ago, I discovered via a Facebook post from one of her cousins, that she’d spent half her life making clay pots and needlepoint lampshades in a secure facility up north. And Jimmy Tudhope had a brief career with an American minor league hockey team before flaming out in a sex-and-drugs scandal. Some days, not having to adult, keep a budget and make any decisions seemed like not such a bad deal. The thing is, after I turned 40, and I began to be whip-sawed by events I could never have imagined, I realized that I had another chance to discover who I really was.

2 December 2025

“Saddle up, Pard. We’re going for a ride.” Bosco Poon, my partner in work and business for thirty-some years, sauntered into my office and dropped a pile of winter gear on my visitor’s chair. “Don’t you look a sight?” I wanted to laugh but knew he’d kick my butt in one way or another if I did. He was sporting a camo tuque, a dark down parka, a red turtleneck and heavy bib overalls tucked into lace-up winter hiking boots. “I gotta do some surveillance in the west end. “ “So?” “Kenora’s off doing an interview and I need a second chair.” He headed for the door. I was just about done for the day, anyway, and I needed a break. My mind was as nimble as cottage cheese. I shucked off my loafers and office clothes, put on a turtleneck and a pair of lined jeans and suited up. I let Seta, our office manager aka ‘she who must be obeyed’ know that we’d both be out for a while. By the time I was done, Bosco was already in the parking lot with the motor running. His favourite 12-year old crap-brown van with the strategically placed rust spots and dents looked like a thousand other low-budget delivery trucks, but the interior was completely tricked out with ergonomic captain’s chairs, an electric motor that would keep us and our coffee warm even though the engine was turned off, front-rear-side mounted cameras feeding into a video system under the dash and fooler window coverings that made the vehicle look empty from the outside. “What’s going down?” He fiddled with his Bluetooth gizmo and peeled out of the driveway. “Check to see if the camera feed’s working.” Which I did. “Supplies.” We had our mobile radios, cell phones and flashlights under the seats. I checked the insulated box between the front seats. It was stocked with a pair of steel thermoses, bottled water, a padded box containing sandwiches and brownies wrapped in cellophane. I knew from the smiley face sticker across the fold that Kenora, one of my private investigators, had baked them. I flipped through the papers on the clipboard hanging from a magnet on the coin tray. By the time I finished my inventory, he was wheeling onto the Gardiner Expressway westbound. “Looks fine to me. What’s this about?” “I’m looking for a Rumanian dude I used to know. Worked auto accident injury insurance scams.” “You needed me for this?” “Seems he’s graduated to defrauding banks. I got a tip about a location in the Junction. Plus, it’s been a while since we had a chat, Bud.” “Chat? Sounds like you’re been in therapy.” “Nope. Working at being married again. Figuring that out.” “Okay, I’ll play. Whaddya want to ‘chat’ about, child-rearing?” “No.” “What? “ “You, Chum.” “Why?” “I’ve been picking up some weird vibes lately.” “Like what?” “You’re preoccupied. Pulled in. I’m not the only one to notice, by the way.” “Who else’s noticed? “Never mind. Your PSA up or something?” “No.” “Business problems?” “No. This last year’s been the best ever. More clients, more investigations completed.” “Uh huh.” Bosco waited until a southbound dump truck passed then pulled a left from Keele Street onto Glenlake Avenue. “So what’s been chapping your ass lately?” He got occupied searching for a parking spot on Oakmount Avenue. “Nothing.” He positioned the van in halfway down a line of rehabbed row houses, tight between a dark Mercury Marquis and a rusted Ford Taurus. “You hear about…” “Don’t care. What’s wrong with your life right now?” “Geez. What’s with the Q&A?” Instead of answering, he fired up the electric generator then took his time arranging his parka behind his head. He flipped open the storage box, pulled out one thermos for himself and handed one to me. I knew his would be one quarter Eagle brand condensed milk, his stakeout staple. Mine would be black, extra strong. I jammed the thermos back into the box. For some reason, I felt jacked up enough already not to need more caffeine. He wasn’t going to let go. “You lost the ability to form rational thought?” “This place brings back memories.” He grunted. And waited. He was good at that. The area he’d chosen used to be part of our patrol zone when we were teamed up in 12 Division. Lots of B&Es, thefts from parked cars, fence line disputes, some ethnic sports grudge stuff. We were on the west side of the park and I knew it was a long cold walk to Keele Street and a bus stop. Did they still run after midnight? I hunkered down, figuring I’d outwait the stubborn bastard. Half an hour passed. Bosco mainly stared out the window. Hungry, I fished out a sandwich, then had a brownie and a cup of java. “You put this together?” “Yeah, with some help.” “It’s good. Remember those clapped-out surveillance vans we spent so much time in?” “Uh huh.” “Did I tell you the one about…” “You forget I asked you a question?” He was getting testy. I couldn’t figure out why. I thought things had been going okay overall. “What the… you gonna talk about paradigm shifts next?” “Don’t demean our friendship with that crap, Bro.” He turned his body towards me, propping his knee against the gear shift. He folded his arms tight across his chest and leaned against the car door. In the light reflected from the street lamp, his face looked more like an axe blade than usual. “Tell me what’s going on. You’ll feel better.” Bosco was going all Reid Interrogation Technique on me. I could keep trying to fake him out, but that had about as much chance of success as me getting him to do a line of blow or an Aqua Velva shooter. If I really pushed back, he’d punch me in the mouth and make me walk back to the office without my coat. “Just say it.” “Fine,” I said. “Hanging around with Audrey and Kenora has made you soft.” “And whatever’s got your globes all shrunk up’s got you so confused you don’t know whether to crap or wind your watch.” “I wish I still smoked.” “Audrey’s the best thing that ever happened to me. Kenora’s the best thing that’s ever happened to you. Admit it.” “Ok.” I turned my head to stare out the side window. Bosco’s relentlessness was beginning to give me the heebie-jeebies. “I know you better than your mama ever did, Jake Barclay. Quit fuckin’ around. What gives?” I blew out a breath, fogging the window. “It’s real simple, Bos. I’m losing my edge.” “What do you mean, ‘edge’?” “When I played high school all and varsity hockey, they used to call me the ‘Cleaver’, because I could cut through anything that got in my way. Lately, it’s like I’m getting soft. Soggy. Maybe it’s an age thing.” “Pecker dysfunction?” Now that made me laugh out loud. He said it all serious and leaned in with a Sigmund Freud stare, all thoughtful and frowning. “Hell, no. You?” “My wife just had a kid who looks exactly like me. So, no. Backatcha.” “I’m…You know what my life used to be like? How I caught Sara-Jane in bed with Lloyd Schomberg after I helped put him away for that boiler-room operation in Woodbridge? Her showing up in the office brought all that shit back, but worse.” “WGAF? She’s been gone for what? Eight, nine years? Why the rebound jim-jams now?” “Kenora’s determined to find that little shit of a brother-in-law of hers.” “So?” “I don’t want her contaminated by anything having to do with my ex-wife.” “Why would she be?” “She’s so bloody-minded. And naïve. Thinks she can solve shit with research and a smile.” “She’s doing okay so far. You getting all Sir Lancelot for her?” “Yeah. That’s what’s wrong,” I said, turning to face him. “She told me you guys had the ‘partner talk’. I never had a relationship with anyone I worked with before.” “Me either. You envious or something?” “I don’t know, Bos.” He poured himself more coffee. Even with the heater on, the air was cold enough so that the hot brew steamed up the windows on the inside. “Is it kind of funky weird or does it make you horny all the time?” Before I could answer, he held up his hand. “Let me tell you what I see. When there’s more than three or four people around, no one who didn’t know you as well as I do or her, for that matter – they wouldn’t be able to tell something’s been going on. She’s deferential, you’re respectful. Most of the time, there’s not much direct eye contact beyond what’s necessary. But when it’s just the three of us, I’ll tell you, every once in a while, it’s like the two of you are connecting with some laser-rope-thing and the room feels real small and I get invisible. Then it’s gone.” “I know. I’ve never had that experience before. No demands, no crazy, either.” “When I told Audrey about it, she got all mooshy and had to blow her nose and then she started kissing me like my face was candy. I’ll be honest. I got wood.” “Kenora does that to me. Watching her mouth when she talks… I mean, I want to hear what she says…” “Most of the time, eh? Bet I know what you’re thinking about the rest of the time.” “True. I guess what freaks me out is that it’s so…undramatic. She’s such a pleasure to be around. I feel comfortable. But she’s not, you know, doing anything to make that happen. When that Mitch guy was stalking her, some of the shit that went down was making me crazy. But I had to let her find her way. She made me promise not to intervene.” “And you left it alone.” “Yes. Then I found out you were pulling some strings in the background. Thanks for that, by the way.” “Nothing to it, Partner. I got your back: I got her back. You guys have mine. It is what it is. You remember the last time you were happy? Not sloppy, Oprah-happy. Deep in your guts.” I bought some time by fussing with the thermos then refilling my coffee cup. “It was after Kenora’s dad’s funeral, when she found out a big piece of information about the mystery man. Then at her house, after her ex had sent back all the cards and family pictures with her face cut out of them.” “Why then?” “I could be there for her, even though she didn’t expect me to do anything. She wants nothing from me.” “And?” “And I want to give her everything. She’s so good for me. To me. I’m scared shitless that I’ll mess it up.” Bosco wiped his mouth with a napkin, tidied up the centre console then stared into my eyes. “You won’t.” He started the engine. “When we were on the Job, you were the steadiest dude I knew. Seldom put a foot wrong. Always reliable.” He did a quick shoulder check then wheeled the van into a U-turn. “Learn to trust yourself again. That’s all any of us want my friend.”

2 December 2025

Note: I seriously started writing The Fifth Man (Book 2 in the Kenora & Jake series) while I was in Ajijic, Mexico in 2019. This post was written in April 2020, when we were still in the thick of pandemic restrictions. I’ve read many articles about how we, as writers, should approach stories where Covid-19 is part of the setting. To include or not to include the pandemic in my novels, that’s the question? Twelve months ago, who could have predicted (and been believed) that life around the globe would sputter to a slowdown such as we’ve never seen. Investment portfolios are in ruins, travel is done for now, holidays and special celebrations are being held via video link and grocery shopping is an exercise in managing personal safety. Thousands of sewists around the world are making cloth pandemic masks and surgical caps because local supplies have run short. Of course, if you write dystopian, fantasy or sci-fi genres, then our current situation may make your world-building easier. For me, not so much. Kenora Tedesco, the female protagonist in my novels, is a private investigator. The house she bought after her divorce is on a small lake north of Toronto. That means she either drives south or takes the commuter train to get to work. She works for a company located in mid-town Toronto – Barclay, Benford & Friday. The firm specializes in industrial risk mitigation. Her love interest, Jake, a retired Metro Police Superintendent, is CEO of the company. The people he employs include lawyers, former police officers, accountants and forensics specialists. Because she’s still considered a rookie, her mentor Bosco Poon, who worked with Jake at Metro and is his business partner, sends Kenora out and about various locations in Toronto to hone her skills at going undercover, interviewing informants or collecting information. Learning to interpret body language and determine deception requires face-to-face interactions. Private investigation is not a desk job. Kenora’s in constant contact with her co-workers, folks on the street, clients, etc. She hangs out at courthouses, restaurants and malls where people she needs to track, investigate or talk to might congregate. There are social events she attends with Jake to schmooze existing and potential clients. She works out, goes to the market and the public library. And she has friends and family, too. I considered whether to have Kenora and Jake isolated due to the virus. Separately, not together. In fact, I started writing a piece where they conducted business from a distance. But it just didn’t work. It felt fake. They have to be out and about to carry on their budding romance. BB&F staff have to investigate people, places and things. Bad stuff has to happen so that she can get herself out of scrapes. Wearing a mask and social distancing as plot devices or sources of conflict? No. I unearthed an old draft where I had her racing home due to a family emergency. Old, as in August 2010. Can you believe it – that’s how long it has taken for me to get to this point! But that was before I realized I’d crammed two books into one. To get one book into a manageable, marketable size, I had to spend a few years surgically separating Book 1 and Book 2. Originally, the plot device/tension-builder was the interruption of her travels by the eruption of the Eyjafjallajökull volcano in Iceland. I would have had to set the story in 2010, which would have required too much research and rewriting. I abandoned that idea. After months of cogitation and false starts, I’m back to my original story line that takes place starting in 2018. There was enough going on in the world to keep things interesting, plot-wise. But freedom to meet and travel are important enough that volcanoes and pandemics just won’t work for me. Kenora doesn’t need a pandemic. She can generate enough action on her own while she tries to be the best PI she can be! So it’s back to the keyboard – not excuses.

25 November 2025

The old man thrills to read the dirty bits where they’re most unexpected. Book shop displays, pale pages splayed wanton behind glass for all to see those slight sweet smuts; words that sound like what they mean - the awe of throb; the thrust of pearly breast, an itch to ‘b’, the hush of saucy whispers simply nothing – not even sweet unless she’s fifteen and fresh, her ink unsmudged. Cookbooks are better than prose, he finds, exposed riots of flushed cooks and rosier fruits – tumbling cherries burst with scarlet sap, the candied apples ooze, caramel toffee drapes a spoon; apricots slump over-ripe on a steamy counter in a drizzled honey bun kitchen - salacious orgies of what ifs, could be. A lap of pooled untempered chocolate, gauchely dark in its shadowy bowl; culturing yogurt teased from tepid milk, turned swollen and bulbous in bellied jars like the softened shape of virgins. After the slather of soft veiny cheese, the smack of cocktails and the seep of fruit juice on diner’s chin, then tussles at the table. Seduced by sweat peas bathed in butter, with lobster tails and a melt of cheddar spuds, the climax a shameless tart of passionfruit and mangoes, An errant breeze - the pages whorl meaty invitations to eat, slurp, stroke berry nipples stemmed by fingers, nails dirty from the dumpster. The words keep coming. A breathy stain of ‘O’ on the window, a blotch of forehead grease - the old man hitches up the cord that holds his pants and turns away, packing an appetite uncontained by empty pockets.

25 November 2025

There’s something about the longer days warming the last snows of winter…poring over seed catalogues and getting ready for spring…considering stowing away the heavier sweaters and testing out some cotton shirts again. All of these mundane activities remind me of how, after 13 years, I still miss my mother so much. This is part one of a letter I’d written to a woman I used to know, who’d told me that when a parent dies, it frees you to become a more complete adult. I’d loathed her with a passion for a long time, but like the intensity of sorrow you feel when someone you love leaves this earth, rage passes too. Hello, Leslie. I’m at home for a couple of days, trying to get my bearings. I sent off the revised copy to the Lazy Writer some time ago but have not heard anything back. I guess that ‘Lazy’ was well chosen. We’ll have to wait and see, I guess. You know, life is very odd. I have been wallowing in misery for years and more recently, obsessing about the decay of my decades-old marriage. I had just got past the stage where I was boringly woeful and had reached the point of feeling some measure of control (isn’t that what the playwrights call hubris?) or at least a state of acceptance about what has been happening. Until last Friday, that is. I received the dreaded middle of the night telephone call from my cousin, who said that my mother had collapsed in her bathroom and had been taken to hospital. I was lying in bed in the dark, trying to absorb the news and praying like a mad fiend that, above all, she would not have any pain, when my cousin phoned back to say that Mom had died. It was like… I was frozen – minimal body functions, slow thought processes, general . Then the emergency room nurse called. He described for me what had happened – they thought it was a massive coronary. She was probably gone by the time the paramedics reached her little house (only 3 or 4 minutes elapsed) and although they tried for 45 minutes to resuscitate her, they were unsuccessful. My aunt (her sister) was with her at home and in the hospital, too, and Mom was surrounded by close friends to the end. They say she looked very peaceful and that her body stayed warm for a long time after her heart finally stopped and they pronounced her. She did not struggle to stay. I’d hoped she’d never leave us, but she was always a strong-willed woman. When my brothers and I arrived on Sunday afternoon (the day after), her place settings for breakfast and lunch were on the dining room table, beside her prayer book. Her address books were sitting there as well, where we could see them right away. The house was neat and there was no sign that this was unexpected, which made us feel abysmally sad but somehow comforted. She was incredibly organized in terms of her will and lists of who was to do what and get what. There was a bit of a kerfuffle because the medical examiner was concerned there may have been some malpractice. Mom had been to her family physician on the Tuesday. He’d found a heart murmur and ordered an emergency EKG but because it was Canada Day and the Stampede was on (hold your horses, folks – everything grinds to a halt for the ‘chucks’!) the test results did not get read. Ok, we said, so what’s the point now anyway – she can’t be helped. Her instructions were specific – no autopsy, no embalming. But the ME was making noises about ‘going in’ to find out what really happened. Uh, no. Now picture this – three adult Type AAs with the suspicion that there definitely was some miscue because of health care funding cuts and a damned cowboy festival. We tracked down the doctor – at a christening, ironically – who was understandably anxious: we spoke at length with the hospital, the medical examiner’s investigator. We were on the edge of a revolt because they did not want to release her body and the thought of her lying in the cold (her arthritis – I know, not rational) was too awful to contemplate (before they took her to the morgue, one of her friends asked if she could put socks on Mom, but was told no, no one else but the ME could authorize anything to be done with/to the body). And of course, we are grieving but unrelenting and articulate, as only Torontonians bent on doing what Mom wanted could be, and on the edge of outrage that we were being stymied, can be. Once we mentioned the L word (litigation) and indicated that we would sue if her wishes were not complied with, the assembled bureaucratic multitudes had the insight to sign off very quickly (with user fees, of course!!!). Thank goodness for the diversion, though. Just cleaning up her house and organizing her possessions was so very very difficult – she had little sticky tags on stuff and had left lots of lists. But it was the ordinary things that we all remembered – a cast iron fry pan from the farm, cutlery, my baby clothes from 52 years ago, clothing. And the pictures – dating back to when she was a child in 1926. Her maternal grandparents’ marriage certificate from 1892. She kept every card, drawing and letter we ever sent her. And I mean every one! The only thing we didn’t locate were the letters that she and my father must have written when he was away during WWII, because we’d found out by accident that she’d known him for four years before they’d married, and they were both scribblers extraordinaire. She also left some journals and notebooks recording her daily activities, so I’ll go through them when I am up to it. I guess the point of this long introduction, is that once again, Mom showed me that just when you think you have reached a stage of being able to bear it all, when you feel, in your arrogance, that you know what pain really is, and you ask how could God burden you with anything worse, there is, in fact, something worse. I loved my mother with all my heart. She was the focal point of my life. Whatever I and my brothers and our children are, we owe to her. My father, who was a lovely man somewhere deep in his chilly poetic soul, left her with four small children in the early 60s, in a small, very Caucasian Ontario farming town, far from her family and friends in Quebec. She didn’t drive and had no skills (farmer’s wife, mother and penny-pincher didn’t count for much), she was black and she was alone without the cachet of being a widow. I remember as a teenager thinking that at least he could have done that for her – died, so that she would have the dignity of being pitied because of something more noble than him having too much emotional sensibility and being too weak to be a proper husband and father, through better and worse. For my Mom, there was never any ‘richer’ back then but there certainly was ‘poorer’, for a long time. She went back to school to become a certified nursing assistant. This woman, whom I remember him calling stupid when his own inadequacy was in full flight, came first in her class and was valedictorian. She won all sorts of awards. Ah, Mom. But what good did that do her? She worked nights for many years so that she could still be home with us during the day, when we needed her. The toll that took on her was tremendous…. to be continued.

25 November 2025

Sound: The misshapen amber ooze inside the stained tissue paper crackles to the counter top in a spray of needles and dried gum. It’s as if the clock has struck three and it’s July 1998 again. The crusty shoulders of Canmore’s hulking Three Sisters mountains are cloaked in rustling pine scrub, alive with the rude exuberance of birdsong. The slow footfalls of our procession are muffled to sad silence by thick leaf-mold on the winding down-sloped path. Brilliant sunshine clatters hot and wrong through creaking pines. Our eyes are buffeted by reflecting heavy shards of copper from the urn. The Bow River – merely a singing stream here – chuckles through mossy gaps in whispering shadows, absorbing the murmurs tumbling from our stiffly praying lips. The last handfuls of my mother’s ashes eddy past a clot of torn red rose petals, swirling over the chattering pebbles and away. Far away. The world will never resonate for me, the way it did before. Taste: The gritty brew frothing in the worn clay cup smelled confusing. At first, the lukewarm liquid tasted of stale root beer with a poke of powdered ginger. Then, for a second, the ‘ow!’ of pulverized hot pepper seeds clawed at the back of the throat, preceding the solace of bitter chocolate coating smoldering taste buds with sensually dark first aid. Competing with the biting oily tang of Seville orange peel, the musty sweetness of ground cinnamon teased the edges of the tongue and disappeared in a salty flourish. Smell: My love is always with me. The steaming iron planes wrinkles from the grey-striped work shirt. Fresh fumes of detergent, fabric softener and baked cloth gust from the ironing board with each hot pass over sleeves, then collar and yoke. Ah! There it is again! Beneath the fragrant tangle of clothes-scents hides the layered secret smell from my beloved’s body. Another swipe of the iron, this time with a shot of steam. The fragrant billowing haze transports that faint exquisite whiff of pheromones to my nose. They stealthily signal-trigger receptors deep inside my prehistoric brain. The fuse ignites, then sizzles through bone from head to groin and back again, in a shock of fiery recollection. Touch: The pads of his thick fingers burnish the knobs of my spine, imprinting heated ovals from nape of neck to swelling curve of waist. A heated slide of palms hovers over shoulders, feather light blows teasing a rush of pulse to the surface of trembling flesh. The vibrato of insistent stroking erases the contours of collar bones. He grounds the prongs of his electric fingers in the fold between my ribs and breast and sparks a breathy hymn from parted lips. His probing humid tongue maps moist paths across my earlobes, then trails from cheeks to cleft of chin downwards, ever downwards. Finally, finally, he captures my melting lips in the taut tasteful prison of a kiss. Sight: Ten days ago, the Christmas pine glowed in the living room window. Pretty parcels tumbled in precious disarray under branches cosseted with garlands, heavy with lights and baubles. Now tossed into the sulk of a January afternoon, half buried with green garbage bags of wrapping paper, the stripped brittle branches poke out of the soiled plowed mounds at the end of the driveway. A spill of spiky twisted needles fills the paper boy’s boot prints on a couple of crushed cones. Random tags of forgotten silver flutter in the sharp breeze. Sap congeals where the bark of the trunk was broken by the teeth of the tree stand. Only a muddle of rabbit tracks circles the forest flotsam.

25 November 2025

I’ve been using the reference texts produced by Angela Ackerman and Becca Puglise for longer than I can remember. Once they introduced One Stop for Writers , there was no going back to gazing out the window searching for inspiration. I may have the ‘writing gene’, like other members in my family, but inspiration does not always come easily. Or it’s stale and unimaginative. This double whammy of writer resources has solved almost all of my technical/craft-type problems. Unfortunately, they can’t get me into my seat with my fingers pressed to the keyboard, laying down pages of attention-grabbing words. Instead, I sneak a chunk of time here and there and frantically try to capture a new scene, plot point or character study in between other things. But here’s where it gets even more interesting. Tools, tools and more tools!

25 November 2025

Edited article, originally published in Crime Scene Magazine, A Sisters in Crime Toronto Chapter Publication I’ve read many series featuring female sleuths like Kinsey Milhone, Mary Russell, Stephanie Plum, Precious Ramotswe and Frankie Drake. None of them resembled the character who’d been inhabiting my creative brain. Wrong age, race, background, values, locale, timeframe. Toni Morrison said, “If there’s a book that you want to read but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” For me, that ‘it’ was Kenora Reinvented. The adage says, “Write what you know”. Hence, Kenora Tedesco is mixed race, black-identifying and middle-aged. Why? Simple. I didn’t have the knowledge or motivation to convincingly write her as a white woman. And despite the urging of an agent who read several early drafts, I couldn’t create an angsty female under thirty who preferred takeout to a well-cooked meal she made herself (or had someone handsome and sexy to cook for her). I’ve been writing Kenora stories since 2008. We’ve grown older together. At forty-two, Kenora Tedesco is the kind of woman you’d notice at an event. Attractive, tall, tastefully dressed, she’s standing off to one side holding a glass of wine, attentive to the ebb and flow of people around her. To all appearances, she’s got it together. Turn back the clock two years, when her tidy suburban existence imploded. Her mother died, her husband dumped her for someone he’d met while Kenora was playing recreational hockey, she got fired and became houseless. Challenged? You bet. Her score on the Life Stress Inventory was off the charts. While some of the details of Kenora’s heroine’s journey into investigations, mystery and second-chance romance may be unique, the major mid-life events she experienced were not. People are exposed to change all the time. They make choices: some are easier, others are gut-wrenching. I wanted her to struggle through setbacks and ‘fish out of water’ scenarios so readers could resonate with her personal and professional growth. Because I’ve worked in the Canadian policing sector for decades, I’m familiar with the frameworks officers operate in. I needed Kenora to have leeway to get into and out of scrapes using her unique talents. Her former job as a middle manager at a Toronto university was boring but paid well. What better career-swerve for a bookish former soccer-mom than starting over in an unfamiliar field, taking on cases law enforcement wouldn’t necessarily investigate? Free-wheeling action, escapades, learning new stuff, glamour! Yes and no. Private investigators must abide by a Code of Conduct and follow procedures. Craft detailed plans. Remain unobtrusive. Take copious notes. All that rule following chafed. Kenora’s mentor Ingraham (Bosco) Poon and her new boss (Francis Xavier (Jake) Barclay) are former senior police officers. They had high expectations. ‘Winging it’—one of her go-to strategies—was no longer an option. When rookie mistakes put her safety, job and a second-chance romance at risk, did she cave? No. A problem-solver, she’s smart, competent and resourceful. She’s also stubborn, skittish and insecure. We all know women like that. Good at what they do. Imperfect but determined. That’s why writing about her was so satisfying. Kenora Reinvented features a feisty, ‘seasoned’ protagonist with scars and plenty of life skills. She starts out thinking she can go it alone, but after several potentially disastrous missteps, she learns to trust her colleagues. With their help and her own creativity and competence, she saves herself. A true heroine in her own sphere, she earns the nickname, Ms. Intrepid. That’s the book I wanted to read and ended up writing.

25 November 2025

In 2000, once we realized that the new century wasn’t going to destroy all of our technology, I decided that I wanted to learn to play a musical instrument. I had an old violin my dad had acquired somewhere, and it had always struck me as exotic and special to be able to make lovely music with a bow and a small wooden box with strings. I was living in a small town before the days of Google. I asked my local librarians if they knew anyone who taught music. They eagerly referred me to a woman who lived in a town twenty minutes away. Was I a successful student? Well, let’s say that I was keen. My instructor was accomplished at piano, violin and viola. I was her only adult pupil. She was also incredibly patient as I sawed my bow every week through rudimentary nursery tunes. Never discouraged, I did learn a few tunes. I switched to a viola, a larger instrument, because holding that dainty violin under my chin made me feel clumsy. I loved the deep sound and the way the vibrations of the chords resonated through my body. My biggest impediment was that I could not read music fast enough to keep time with the rhythm of the songs I weas trying to learn. I can speed read literature like a champ, but those black and white notes on the page were truly a foreign language to me. I resorted to memorization. That worked for a while but whenever a new song was introduced, I felt like I was back in kindergarten. What I found out later is that my instructor had a class of musical prodigies. Most were under twelve years old. They could decode the notes of the most complex piece like they were reading a comic book. We had a common task though – preparing for an outdoor concert at a park by the Barrie waterfront. On a glorious summer afternoon, the rest of the class and I played a mini concert. It had taken me all summer to memorize Pachelbel’s Canon in D Minor but once I got carried away by the beauty of the music, I could get through playing it without stumbling too badly. Our audience was an assortment of parents and random visitors who applauded loudly after we were done. Whenever I look at that photo and remember how I stood out from my young music-mates, I smile with pride that I didn’t embarrass myself at my first—and last—viola recital.

18 November 2025

Suspended over Gull Lake is a long cedar dock that juts away from the moss-filmed rocky shoulders of the shore. A scarred wooden rowboat is trussed at the bow to a rusted wharf ring. Dew-damp spider webs across the gunwales shiver in the breath of breeze. A bloated, cocktail-cherry sun pushes through a jagged cleft between the mountains. Shadowy evergreens matt the hilly cheeks of the Muskoka Forest like a weekend beard. My footfalls on the warming planks, though light and tentative, send shivers across the skin of the placid lake. Scent from the shady edge of the dock swirls over me – cedar, mud, the lavender I planted years ago. When I still myself and shut my eyes, the busy silence resonates against my eardrums. It’s five thirty in the morning in the middle of July and I’m all alone. I turn my head towards a rustling sound at my back. There’s something under the red currant bush. I stand quietly, foggy breath swirling out of my mouth, wishing I’d worn my glasses. Finally, a pair of skunks waddles across the path leading from the cottage. They smell something and stop to look at me poised in the middle of the dock, then – perhaps because they, too, sense that I’ve lost track of my own importance - they amble, tails down, into the brush behind the boathouse. The sun is that much higher when I turn back with a crick in my neck from motionlessness. The marshmallow haze coating the far shore is breaking up beyond the shallows, disturbed by the crowds of mouths of feeding fish. Further up the hill, round bales of fog tumble down the gravel wash, unraveling to nothing over the felled logs by the beaver dam. As I shake off the last clogs of sleep and give up on keeping my feet dry, I catch sight of the deeps beyond the diving platform warming to navy serge under the sunlight. Someone told me long ago – was it Frankie or Pa – that if you tilt your head to one side and half-way squint, the first ripples of the day look like fractures on the plate-glass water. It’s true; they do. Why can’t I remember who said that? It probably doesn’t matter. The misty bits and all the hard edges of dark have burned off to golden air. A toilet flushes in the cabin. Up by the ridge at the end of the lake where the days begin, a red-tailed hawk coasts the thermals then plunges into the trees. There’s a scream, a momentary hush, then the marsh-quiet starts to crack under the catcalls of other wild things in the morning. Amidst that smell of rotting leaves the earth is giving up its cool. Something mottled and sinuous glides around my right ankle and disappears under the dock before I can focus my eyes; a hare bolts for the trees from yesterday’s fire pit. Screen doors slam. The sharp, high morning chatter of kids skittering across the night-cold kitchen floor cuts what’s left of the silence and I smell the fumes of perked coffee. A trio of crows argues over the broken carcass of a crab behind the old boathouse. The lake is alive with endless rags of glittering waves. I, too, will have another day.

17 November 2025

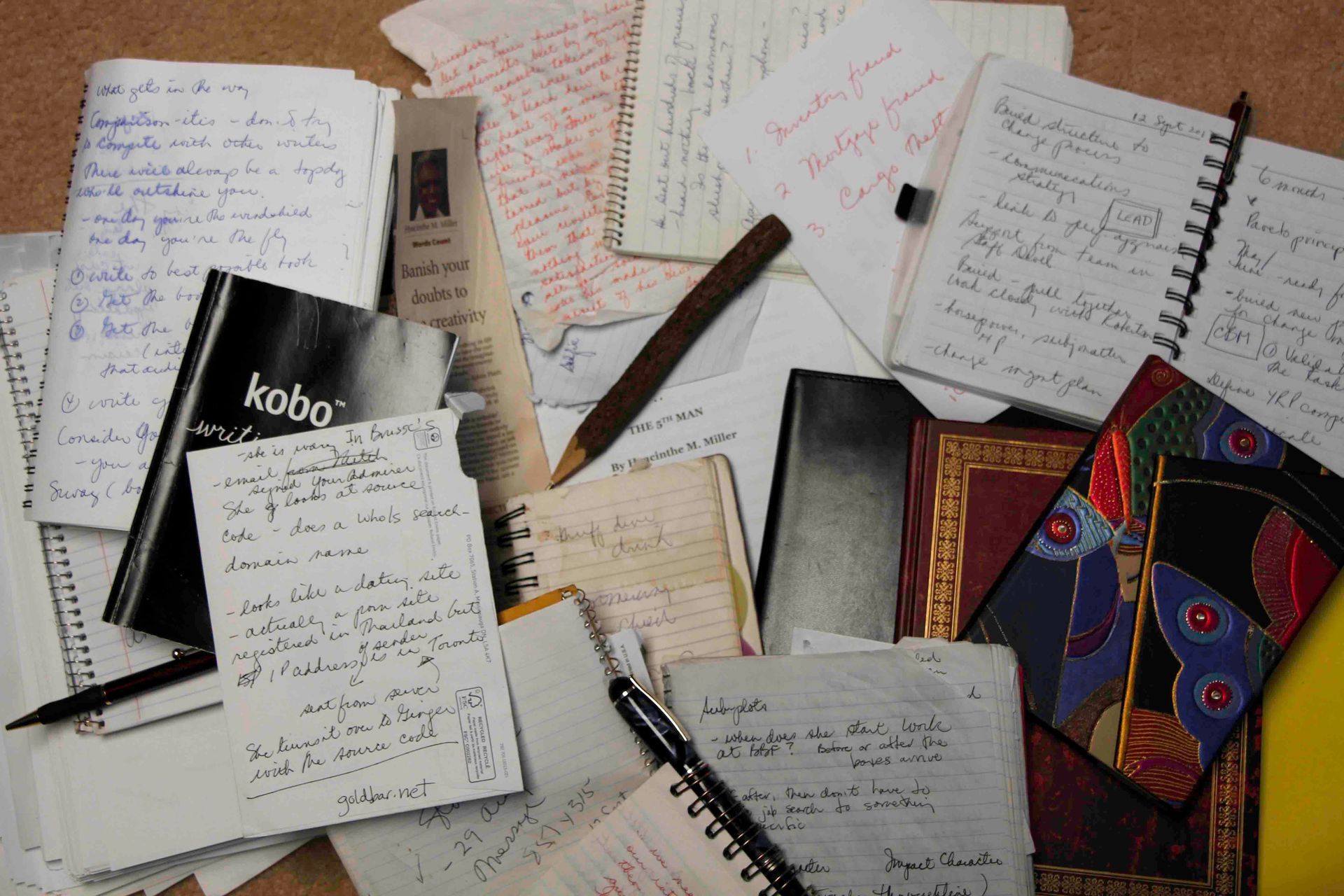

I’ve been writing short and long fiction for decades, but I never was much of a planner. I have boxes of dollar store notebooks and steno pads crammed with notes and story starter paragraphs that went nowhere. Others were incorporated into my completed novels or they are part of works in progress (and I have dozens!). My go-to software was Microsoft Word on a Windows computer. However, the longer my documents got, the more unruly Word behaved. My default was to pound out a few thousand words, give the file a name and date then save it. The end result was a messy directory with multiple folders. I didn’t like that disorganized flea market vibe. Using Explorer to search for word strings was maddening. Arranging my ideas into a logical flow before starting a project was time-consuming and took the joy out of writing. I struggled with Excel spreadsheets, spending more hours configuring columns and cells than creating stories. Then I tried Pages. While it was less frustrating, I was impatient with the learning curve. I went back to Word. Easier? Not really. The original outline for the first draft of my novel ended up as an eighteen-page table. Large tables are manageable as eels – the content boxes change shape as you add text. Besides, the final draft of Kenora Reinvented didn’t end up conforming to the outline. Here’s what I did to get organized. I switched from Windows computers to an Apple iMac desktop and MacBook Pro laptop. I won’t go into rhapsodies about how seamless the Apple ecosystem is compared to what I was using previously, but for someone like me with an undisciplined mind, streamlining my writing process made life easier. Collecting ideas. Apple Notes, Drafts app. Both can be installed on handheld devices, laptops and desktops and sync data automatically. Drafts has an excellent dictation app and a browser widget that lets you save URLs and web copy. I can also Airdrop items between devices, take a screenshot, bookmark websites, save into the apps or as a PDF in Books. Planning. Story Planner ($10 USD). Works on iPhone, iPad and Mac. You can access your project outlines from any of your devices. You can also choose where you want your files saved – on your computer, in the cloud, etc. I downloaded Plottr ($25 USD), a tool featuring drag & drop visual timelines, index cards, character/place tracking, outline builder and templates (12 Chapter mystery, Hero’s Journey, etc.) Writing. Scrivener ($67 CAD – regular deals for Black Friday). Windows, IOS and Mac versions and plenty of free templates. Clean interface. Composing is a breeze. You can drag and drop scenes, collect research, links, photos and maps. Don’t get discouraged by the learning curve – there’s a 30-day trial period. Storage. Dropbox ($144 USD a year for 2T) I save, share and access files from my phone, iPad and computers. I use Selective Sync and only save the Dropbox files I use regularly to my devices. I also use the Sync software (Canadian) because I’m afraid of losing a single document, iCloud for short pieces and photos, Google and Amazon photos (free but not always user friendly). Formatting. Vellum ($339 CAD – to produce unlimited print and eBooks). Only available for Mac OS. Easy to import a text document, format then upload for ebooks. And print books of various sizes. The software gets better all the time. Yes, it’s a big investment but it can also save time and money. There’s a free trial available. Writing materials. Dollarama is an under-appreciated resource for ‘old school’ writing supplies like notebooks and pens.

9 November 2025

I remember 1956. I remember 1956 because I was young, growing fast and usually hungry. My youngest brother – a chubby, happy guy – had been born in February. Those were the days when pregnant women were put to sleep to give birth, and children weren’t allowed inside the hospital, except as patients. My dad held my hand as we stood in the thick snow outside the nursery window and a matron in a long-sleeved starched uniform held up the blue-swaddled bundle as if he was a ham on display. I remember that I wore a dark brown hand-me-down coat with a fake black Persian lamb collar. My rubber over-the-shoe boots zipped up from the toes halfway up my skinny calves. I remember that my fingers and toes always felt thick and stiff in winter, no matter how many pairs of hand-knitted mittens or socks I wore. We were living in an old farmhouse in Ontario Wine Country. My father – always the dreamer – had spied the ‘for sale’ advertisement in a weekend newspaper in Montreal, and had decided that if he couldn’t be a coffee farmer in Liberia (thank you, Mom, for saying no to that insanity), he could be a fruit farmer in the Niagara Peninsula. Back then, the Queen Elizabeth highway was more like a two-lane suburban road, but he set out after his machinist job on a Friday night, drove the old Studebaker half the night, walked the 16 acres and decided to buy it. Without consulting my mother, of course, because she undoubtedly would have said that the idea was madness. We left behind all of the family we’d ever had – uncles, aunts, cousins, and our community – to start over in rural Ontario. We were dirt poor but stone rich on that blighted piece of property. There was a house – barely. It was poorly insulated, with a leviathan furnace in the basement complete with a coal bin. Thin concrete floors over dirt. No running water – unless you’d call an indoor pump in the cellar, ‘running’. No indoor toilet, no central heating. An attic that turned into a sauna in the summer and grew icicles in the winter. My mother was a city girl, convent school educated. She didn’t have a driver’s licence and was stuck at the farmhouse with four children under twelve. I was the eldest, but oblivious as only a bookworm on the cusp of puberty could be. She died before I could gather the courage to ask her what it was really like back then, and push for her to tell me the unvarnished truth. With a family of six and no indoor plumbing, my mother was seldom still. Sometimes though, after school, when the baby was asleep, Mom would stop what she was doing for a moment and sit at the kitchen table with her hands in her lap, staring into the air. I’d ask what was wrong. She’d smile a tiny smile and wrap me in a mother-fragrant hug. Her hair was soft against my cheek. Mom would give me that special raised eyebrow. “I have something to show you,” she’d say, as if it were the first time ever. “Go wash your hands and face.” She’d flip up the kitchen curtain to make sure my younger brothers were within earshot and hadn’t impaled themselves on a farm implement. Then she’d turn off the stove and climb slowly up the narrow wooden stairs to the attic, wiping her fingers on her apron, her shoes squeaking on the rubber risers. The narrow stairway smelled of soup. She would stop about four steps from the top and wait for a minute, head bowed, her breath loud in the shadowy passage. Beside her right shoulder was a door sunk into the dark wood paneling. There was a small brass handle in the middle, with pointy edges like a small bird’s beak. She’d turn the handle, then fold the door back so that it wouldn’t bang. I’d push by to stand a step higher up so I could see inside. She’d stretch her arm in – it was as if her fingers had eyes – and she’d tug the rusty chain that dangled from the rafters. The lemony light would cast her smooth brown features into sharp shadows. Dust swirled around the bare bulb, disappearing deep into the shadowy attic and reappearing in the beams of light from random gaps in the shingles. Our breath fluttered the cobwebs like pale sails. I remember shivering, wondering if we were disturbing someone who hid there and who’d only come out when the door wasn’t open.

8 November 2025

One hip pressed against the wall, her palm warm on my shoulder to steady herself, she’d ease out a square leather case with silver fittings glittering at the corners. It had one of those swing-down catches with a little crooked tooth. The tooth snugged into a metal loop on the front. We’d sit down on the stairs, knees touching, the box between us. She’d nod and gesture ‘go ahead’ with two fingers. I’d wipe my hands on the lap of my brick-patterned skirt then gently brush time’s dust off the top with the hem of my blouse, swing up the silver hook and lift the lid. She’d usually turn away for a while to stare over my head at something I couldn’t see. I’d guessed perhaps she was seeing ghosts, but when I looked up the stairs, there was nothing there. “My mother was a dainty woman,” Mom would say softly, wiping her eyes with the corner of her apron, not looking at me. Somehow, my self-absorbed self understood that I should be reverent, that I shouldn’t rush. So we’d sit in the dusty quiet and stare into the shadows of the box, waiting. I shivered when I touched the flimsy wrappings, held loosely with thin faded ribbons or plain parcel string, knowing they held her memories. The rustling papers stirred up a confusion of scent – lavender, lemon, rose and then leather. I lifted out the treasures, one by one. A thin Blessed Virgin Mary cradling baby Jesus between her ivory arms. Packs of brittle greeting cards with stained edges, red-striped airmail letters cramped with Dad’s blue-black writing, over-stamped with ‘Allied Forces Overseas’. A carved wooden Sphinx the size of my hand, branded ‘made in Egypt’. Three faded roses bound with lace to a slim silvery wrist-band. A dark brown baby shoe worn down at the heels. I picked up a photograph tucked against a corner. The date in the pinked margin read February 1938. The camera had caught her dark oval face and her unblinking gaze under a solemn brow. Grandmother’s thick wavy hair was pinned up under a fancy hat. Her fingers gripped the back of a velvet chair. Less than 12 months later, she would sit in a dentist’s chair for a wisdom tooth extraction and not awaken from the anesthetic. My mother was 19 years old, guardian three young siblings to keep safe from the social service authorities who wanted them sent to an orphanage. She bore the weight of that death all of her life. I know that now. In comparison, the box that lay in my damp hands was feather-light. I’d peel back the layers of tissue and there they were – my grandmother’s shoes. They were tiny – size 4, I think – black, with 18 shiny leather buttons marching from the arch to the ankle. They were creased but hardly worn, just enough to give off that comforting used smell. The heels were the width of three of my fingers, about two inches high. I traced the seams and fancy threading along the tongues. I gleaned the cobbler’s name on the instep with my fingers, as if the words were Braille: Savage Shoes. There was no question of me putting them on. At age eleven I was almost as tall as my mother. Already my feet were bigger than hers. Mom would sometimes pick up a packet of letters and fan through them like they were leaves, only with writing. I remember asking her what they were. She’d said, “Your father wrote such beautiful poetry to me when we first met,” with a sad profundity even I could comprehend. And I would look from her beautiful chapped hands that were almost never still, to the mute epistles in her lap, wishing I could know what she was thinking, what she was wishing. My eyes would feel hot and full and my ears would throb. We would rest there on the steps until my brothers banged through the screen door or the milkman came or the telephone rang – two long, two short. Too short. Then she would motion for me to put everything away. She’d push the box back into the shadows, snap off the light and close the door with a sigh. I would sigh too, my skinny shoulders rising and falling in time with hers. Leaning against the step, she would fold me to her chest, the sweet powdery smell of her body filling my nose, displacing the scent of our pasts. Back then I thought it odd that she never wanted to hold my Grandmother’s ‘good’ shoes. But when my mother died too soon, I began to understand the power of possessions so personal. Even today, when I venture to our storeroom to go through the things that I’ve stored since her passing, they hold a resonance that brings back that pulsing throb, the thickness in my throat, the tremor of longing in my fingers. Oh, Mom. I tuck them back into their boxes and seal the lids with fresh tape. Perhaps next year I’ll try again.

5 November 2025

I love bacon. Not the pale, store-bought, watery then brittle-when-cooked nitrate stuffed strips, but the old-fashioned kind that smells like meat when you fry it in a pan and that lingers in your mouth, with a subtle, sensual pork taste. Sure, you can get it at the larger farmers’ markets, but who wants to drive for half an hour and queue for 15 minutes to buy half a kilo of tasty smoked goodness? BB&F surprised me with a bonus at the end of my first year of employment. Instead of setting it aside for a rainy day, I decided to take my friend Maggie’s advice and buy something for myself to a Kamado Joe Classic III charcoal grill with all the accessories. Their tagline is: “A Kamado Isn't Just A Grill. It’s A Lifestyle.” Of course, I jumped in with both feet. Why bother with something as prosaic as grilled chicken when I could go big? I ventured online to sites like Amazingribs.com and Reddit and watched countless Smoking Dad BBQ YouTube videos. I read the spirited discussions about the merits of home-curing and different varieties of charcoal. I read countless blogs penned by adventurous women and men who were curing their own meats and making sausage. Yowza. And who is the inspiration for all this innovative grinding of meats into chilled bowls? I confess that I’m wild about Michael Ruhlman. Not MR himself, but his approach to food preparation. I learned that the guru of goodness is a man from New York, who graduated from Duke University with a degree in literature. He’s a prolific author, but that’s not why I’d do his laundry. How can you not admire someone who said: “he best things in life happen when you get carried away.” After drooling over the blogs regaling us with Charcutepalooza tales, I decided to buy his book, Charcuterie . I sourced a pork belly from Vinces’ Market in Sharon. The thing weighed almost 7 kilos and came complete with a thick skin that took me a while to surgically remove while not slicing off my fingers in the process. The tiny nipples on the belly were a bit of a turnoff, but I persevered. I divided the belly into three chunks, that fit easily into large Ziploc bags. Post-cure, the bellies were firm and well streaked with fat, but what was best of all were the thick layers of meat in between. I used a mixture of Insta-Cure, brown sugar, salt and fresh-toasted ground red/black/white peppers, cardamom and juniper berries. I double-bagged everything and tucked them onto a shelf in the downstairs fridge, weighed down by a case of pink grapefruit cups for 8 days. I turned the packages every day and watched the meat transforming from soft and flabby to firm and muscular-looking. Sounds like a workout regimen! Cold smoked for 8 hours over pecan wood and – wow. The only issue for me is getting the slices thin enough. I splurged on a slicer so now I’m cranking out gourmet bacon slices. The Food Network lists 50 ways to add bacon to recipes – here’s the link . Bacon guacamole, maple bacon donuts, bacon ice cream, bacon popcorn, chocolate dipped bacon, bacon wrapped dates, bacon wrapped tater tots, dips and bread – oh goodness, I’m in love. Then again, I’ve been surfing for salted caramel and chocolate recipes. Dieting be damned. The flavour punch of salty sweet, meaty, crunchy would be amazing.

3 November 2025

Before they invented big-screen televisions and botulism was something you never wanted to find in your food, never mind inject into your wrinkles, Mondays were washdays. In the damp concrete-floored, low-ceilinged cave that was our basement, my mother had an Easy brand wringer washing machine with an agitator the size of an outboard boat motor. The machine’s electrical cord was the size of my ten-year-old wrist and when you plugged it in, the whole contraption made the most wonderfully frightening grinding roar as it mashed up the dirty clothes into a sudsy pudding. As the eldest, I got to feed the corners of the bed sheets into the finger-mangling rollers of the wringer, every shove forward an audacious flirt with danger. Would it be painful if my hand got dragged in? I can vouch for the relentless undertow of the spinning rubber cylinders, but they actually didn’t hurt that much. Once the soiled water had been squished from the load, they were dropped into a huge tub filled either with a dilute blend of Reckitt’s fabric blue or bunch of herbs like lavender (remember, this was way before bottled fabric softener). It was time to empty the tub and refill it with clean water. Since we had no indoor plumbing, that meant a couple of trips to the pump in the corner of the cellar to fill up the galvanized tin pail. We were eco-friendly before it because the in-thing to do – we always washed in cold water! I’m not sure of the formulation of the Sunlight soap bars we used to scrub stains, but they were strong enough to strip off the epidermis if you left your hands un-rinsed for long. The scent of sun-dried laundry was glorious. Winters, though, were a chore. Baskets of damp clothing had to be manhandled to the back porch and hung quickly on the plastic-coated line before fingers grew stiff with cold. At the end of the day, everything was frozen into cardboard cutouts of their thawed shapes, sharp enough to wound the unwary. Of course they couldn’t be folded. Instead, we took turns wrestling them into the house. Sometimes, depending on how cool and dry it was inside, they’d hang for days on lines of cord criss-crossed under the basement ceiling.