The Covenant - Part 1

This story begins with a lie. In Latin, mostly. With a bit of English and some franglais thrown in for the pew-fillers seeking refuge from the frigid bluster of a Montreal winter.

On January 19th, 1946, a pair of twenty-five-year-old orphans slipped into the vestibule of St. Anthony's Parish church on rue Saint-Antoine. They stamped snow from their feet, hung their heavy coats in the cloakroom then milled about in the incense-scented dimness.

She wore white, of course. White pumps and silk stockings gifted from her Girl Guide troupe, a simple lace gown that cost a month's wages and a filmy chapel veil tatted by Ma Wheattle, president of the Catholic Women's League. Rail-thin, her work-chapped fingers scented and gloved, the bride clutched a posy of pale flowers and recited a silent prayer to her Guardian Angel. Clad in a natty, double-breasted suit, her silent companion adjusted his trouser creases and stared straight ahead.

The altar boys elbowed each other as they lit candles in the sanctuary. With a frowning shush, the elderly priest motioned to the groom. Spine soldier-straight, he strode to the altar rail. In the choir loft, the organ wheezed to life. An old family friend, an honorary uncle, proudly stood in for the bride's long-dead parents. He hushed her three younger siblings, waved them toward their pews, then solemnly walked the bride up the long stone aisle to give her away.

Ah yes, the sacrament of holy matrimony. The "covenant by which a man and a woman establish between themselves a partnership of the whole of life and which is ordered by its nature to the good of the spouses and the procreation and education of offspring". In which man and woman were intended to cleave one to the other for a lifetime. Beatrice pledged to ‘forsake all others’, to be faithful and bear his children.

She stared at his handsome face and with a tremulous smile, murmured, “I give you my all.”

She meant it. Those monthly novenas to Saint Joseph, the lonely prayers to St. Raphael, the scores of candles lit during those years scarred by grief and the Great Depression had been worth each hard-earned coin and calloused knee.

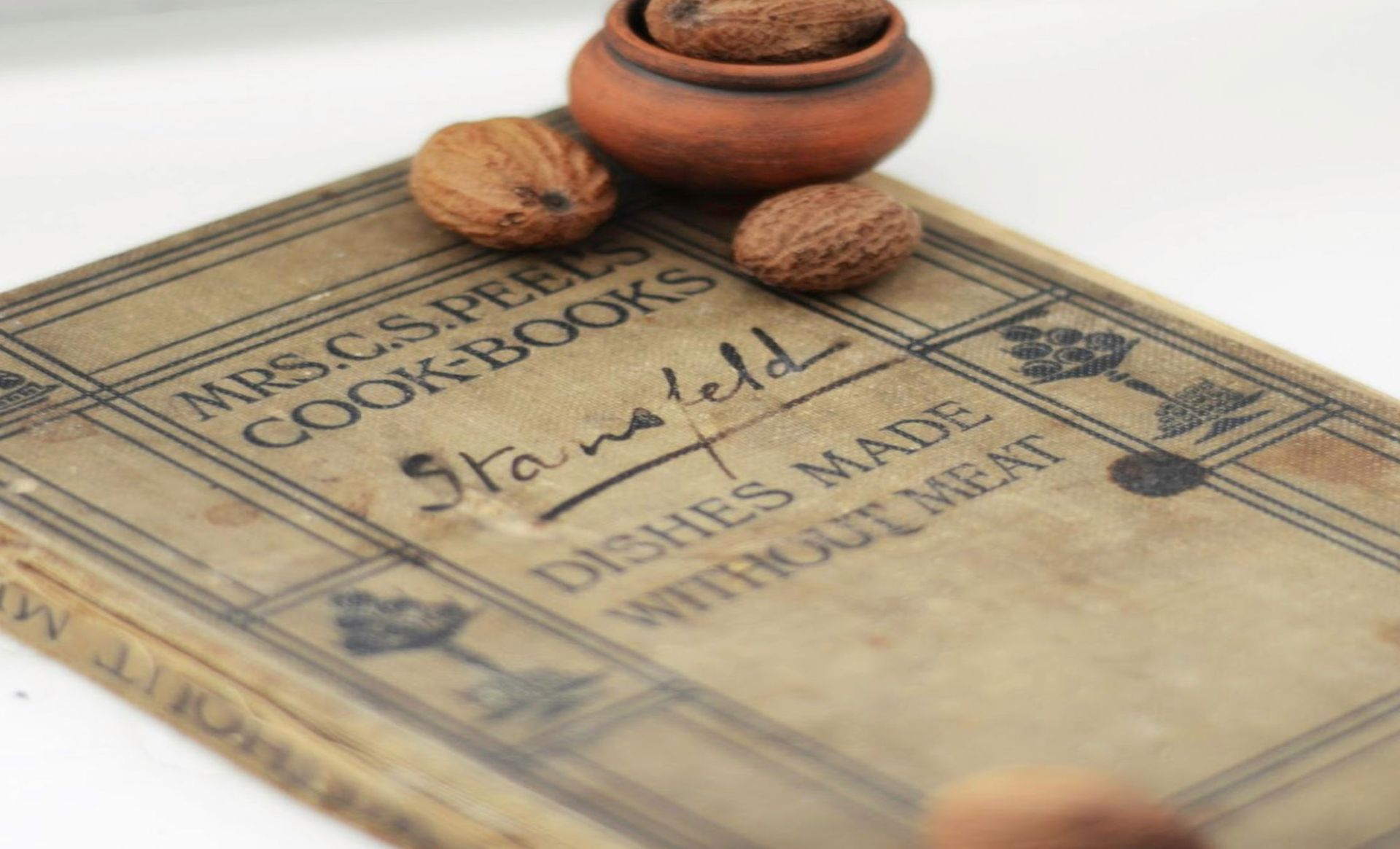

Beatrice had kept her small family together since the age of nineteen. While she worked three jobs, the ‘uncles’ and ‘aunties’ of the Negro Community Centre fended off inquisitive social workers with orphanages on their agenda. She’d smile as she asked the butcher for ‘bones for the dog’ they did not have, then carefully eke soup or hash or a pot pie from the meat scraps. When the cupboards were nearly bare, the children were fed first; she was sustained by the rightness of what she was doing. And now she was getting married. In the house of her God. No matter that they hardly knew one another. They’d been brought together for a reason. Her faith had seen her through so far. Would see her through. No matter what, she believed.

Holding her hand in his calloused palm, Anthony took a deep breath then repeated Beatrice’s words. He slipped a gold circlet on her finger and said, without meeting his bride’s hopeful gaze, “I take thee for my lawful wife, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, until death do us part.”

If only. If only we could hit 'rewind'. He lied. He had no all to give.

His vow was broken as the phrase left his lips. The lie was one of omission, but mendacious nevertheless. Beneath that tailored navy blue wool, the crisp white shirt and spit-shined brogues, Anthony was a ghost with a captivating smile. He had form. He had substance, too; just not enough.

What kind of person could he have been if his father’s legs hadn’t been cut off by a cane-hauling train in Cuba? If he hadn't languished in a hard chair for three days at his sickly mother’s bedside, not leaving except to urinate behind their neat wooden house? Three days—forever for a ten-year-old boy—spent stroking her arm and begging her to awaken. But she’d already given up and died. What if he hadn't been fostered by relatives who treated him like a human donkey? They’d threatened that sensitive, love-starved boy with the Bible and tried to thrash his artistry away. When they caught him reading the Classics, they starved him of food. Would there have been more of him to share if he hadn't lied about his age and joined the Corps of Royal Engineers as a sapper? He’d trained in Chatham, Kent in England, where he wrote poetry on the backs of old envelopes. A curly-haired Land Girl in mufti taught him to dance. He learned that Satan didn’t care about him. And in the shadow of the Sphinx, what remained of his youth was blighted with sand flies and spattered with the blood of his falling comrades.

Who knew that only most of him would return from overseas to be demobbed in Montreal? Those two orphans were so hopeful. They tried. Dear God, how they tried.

A scant nine months after the wedding, their daughter was born. Anthony had taken ship from Southampton, England, two weeks before. He had a trade and found work as a machinist. Master of his own house, he overflowed their bookshelves with leather Reader's Digest volumes. Beatrice, a proud young matron, kept house in the old family apartment on St. James Street.

Out of habit, she ‘made do’, using every part of a chicken except the squawk. She sewed and knit for the children and taught herself to make preserves to keep the larder filled. They hosted potluck parties. Family and friends, music and food, debates and laughter. Three years later, a son arrived. Another boy—one whose background was shaded with mystery—was ‘adopted’. There were five around the table. For a time, it seemed like equilibrium had been restored.

Then Anthony bought a plot of land on the South Shore. Located in the middle of an empty field, the settlement of Mackayville would eventually grow into a suburb populated by rough-and-tumble labourers who favoured driveway auto repair and large dogs. He drafted plans for a modest wood-framed house with a concrete block foundation, red Insulbrick siding and asbestos roof shingles.

Most weekends, he slept in a tent with his tools beside piles of two-by-fours. His buddies from work or from the nearby Caughnawaga Reserve would drop by to help. Even though he was more of a handyman than a builder, he couldn’t abide the sloppiness of well-meaning helpers fueled by Carling Black Label beer.

When the house was ‘finished’, it resembled a sharecropper’s cottage more than anything else. There was a well in the back and a hand pump in the kitchen. An ice box sat in the lean-to pantry. Meals were prepared on a wood-burning cast iron cook stove. It was months before the electricity worked reliably. The place was drafty and the oil furnace smoked. Nothing but weeds grew in the yard: they were literally dirt poor. Something always wanted fixing or they needed another cord of wood. Everything was more expensive. In 1953, with three youngsters underfoot, Beatrice was a pioneer wife not thirty miles from her network of family and friends and the largest city in Canada.

She adjusted. Hadn’t she said, ‘for better or worse’? Being taunted for being coloured cut deep. The loneliness she kept at bay by keeping busy. Eighteen months’ later, ‘better’ returned. Her husband grew tired of commuting over the Jacques Cartier bridge, sold the do-it-yourselfer and moved them into a bright walk-up on Lusignan Street. Beatrice was back in her element. They had modern conveniences. No one called them names. The children were healthy and exuberant. Life became more stable year-by-year, but Anthony chafed. He’d never known a ‘normal’ that lasted so long.

He swept into the apartment after work one Saturday afternoon in 1954 and handed his wife a box of Cadbury’s Assorted Milk Chocolates.

“Thank you. But why?” It wasn’t her birthday or their anniversary. And Anthony wasn’t a spontaneous man.

With a shy smile, he announced that he wanted to start a coffee plantation. Or perhaps harvest rubber. The whole family could work their acreage. Where? The Republic of Liberia.

“Liberia? In Africa?” Beatrice said.

“Yes. The Motherland. Think of the opportunity. We’d be among our own people.”

She glanced around their neat apartment, at their children colouring at the kitchen table. At the handful of spring flowers in a jar by the new RCA Victor radio. She bowed her head for a moment then looked at the earnest face of her husband of seven years.

“We’d die there, so far away from everyone. From my family. Our people are here. No.”

He stared into her eyes then said, “I’m going to write some letters,” and left the room.

Beatrice was a good wife. She asked no questions. He talked about re-enlisting to fight in the Korean War. She reminded him of his family obligations. He buried himself in his papers. The familiar rhythms of life resumed. A few months later, the first of the pale blue aerogramme envelopes arrived.

Recent Posts