The Covenant - Part 2

On a rainy Friday evening the following June, Anthony announced he was going away for a few days. “Don’t worry. I’ll be back with a surprise. I promise.”

He returned on Sunday evening flourishing a thick Manila envelope, travel-weary but jubilant. He kissed his wife on the cheek, not something he usually did outside their bedroom.

“Here.”

Beatrice wiped her hands on her apron, relocated the cat from her chair to the floor, then sat and peered at the pages filled with legal jargon and map coordinates. Anthony shoved a photo into her hand. Indeed, he’d been too modest. The ‘surprise’ was cataclysmic.

At least this time, the house was already built. Red insulbrick again, but it looked sturdy, with two storeys covered by a shingled barn roof. Windows on each side of a door with no stairs looked like empty eyes. There were apple trees in the front yard. A tractor was parked on the gravel driveway.

“Sixteen acres of orchards. Sour cherries, peaches, pears. Grape vines. A cistern. All the farm equipment. Our own creek.” His brown eyes crinkled with delight.

‘Our’. Beatrice hadn’t seen him so happy in years. He kept saying, ‘our’. She knew she should try to share his joy, but with every word he spoke, her heart shriveled.

Glancing at the picture again, she said, “Where?”

Nothing changed. Except that everything had changed. He unfolded a worn map. Province of Ontario. He jabbed his finger beneath a speck of letters: Beamsville.

“Our future. It will be good.”

That was a lie.

***

Beatrice gazed at the relentless green of forest and fields, wondering at the resolve of this man beside her who was more of a stranger to her than before. She shivered. Every place she’d ever known, everyone she’d loved except for her children, was out of reach. Even the cat had run off before the last box of books was packed in the Studebaker’s trunk. Anthony wheeled the car from a tarred country road past a battered aluminum mailbox on a post by the ditch and up a narrow lane to their new home.

Six months before, he’d read an advertisement offering ‘productive farmland for sale’. He’d driven eight hours each way from Montreal—four hundred miles—to buy his dream with the last of their savings. During the intervening months, he’d been so sweet. Tried out intermittent little gestures, as if he’d been practicing. Promised to teach her to drive. Told her they wouldn’t be pinching pennies forever. She’d wept in private, begged her friends to come visit, and stopped going to Mass. Why bother? God had forsaken her. They’d arrived in rural nowhere as night was falling, exhausted and numb. They had groceries to tide them over for a few days and as many personal goods as they could cram in.

While the children slept in the back seat, Anthony grabbed Beatrice’s hand and tugged her up the six worn planks at the side entrance. She looked askance at the sagging clothes line attached to the wall and the path leading to a narrow shed at the edge of the orchard. The entrance door opened with a shriek. Inside smelled of old dog and stale heat. Their footfalls echoed on the red and yellow linoleum. There was no other sound but the buzz of flies trapped between the screen and panes of glass in the double windows. He flicked the light switch.

“Guess they forgot to turn on the power,” he said, taking a flashlight from his pocket. She slid her hand from his and fingered a gingham curtain the colour of old blood.

They toured the house. It was so much less than Beatrice had hoped, but just about what she’d come to expect. There was a green Formica table and four chairs in the kitchen, an electric stove and refrigerator. But instead of a faucet and taps by the cast iron sink, there was a hand pump. She blinked back tears as she climbed a flight of wooden stairs to the bedrooms. When she looked up at the uninsulated ceiling, she saw slivers of moon through the wooden slats.

“I’ll go get the children,” she said, and trudged into the blur of her future.

***

The day school started, sun blazed in the autumn sky. Beatrice’s morning sickness was over. She’d learned how to operate the wringer washer in the dirt-floored cellar without mangling her arms. And in the heat of summer, hanging load upon load of damp laundry hadn’t been so bad.

‘For richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health’.

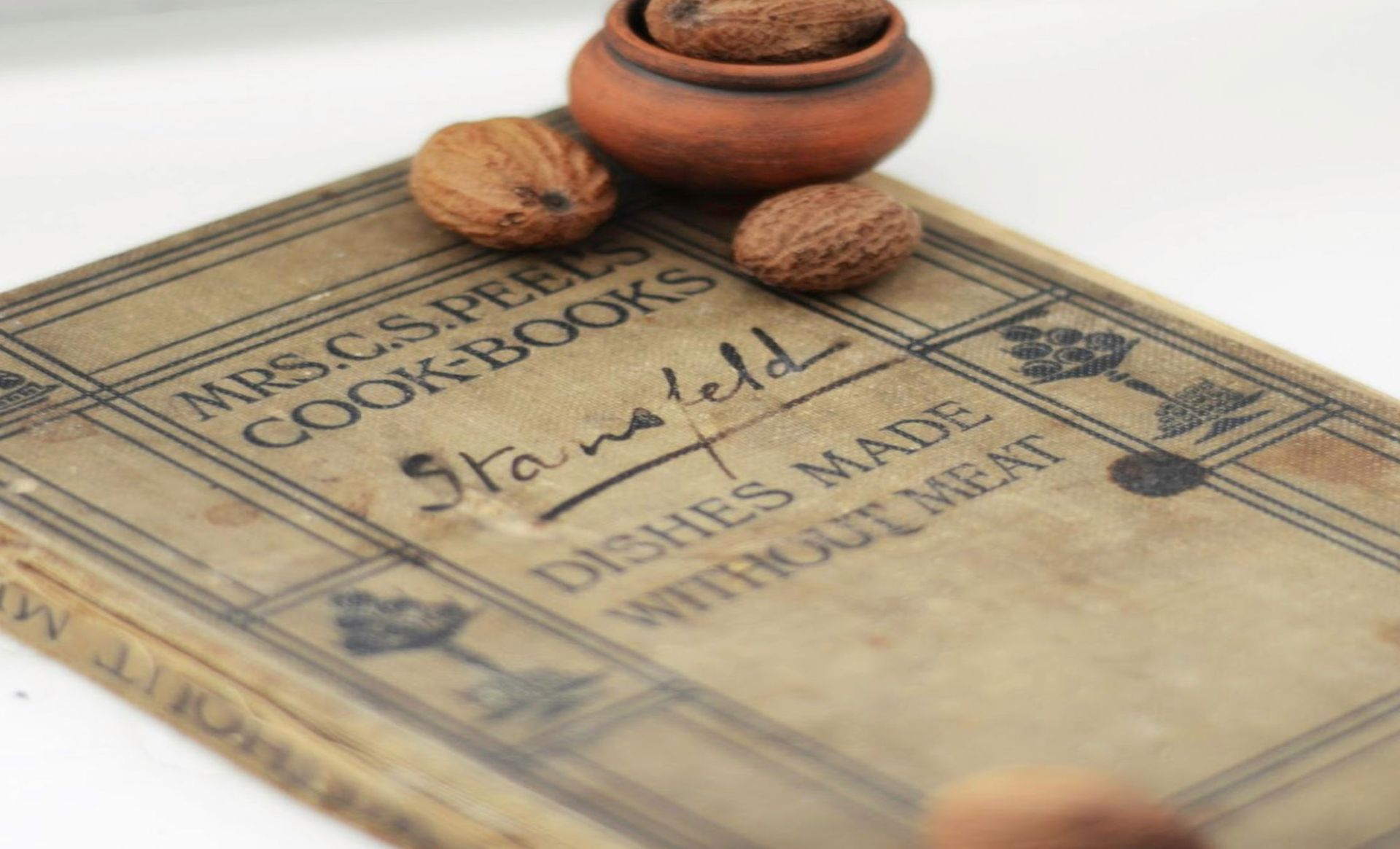

Weary of housework and picking rocks from the cherry orchard, she decided to repaint their name on the mailbox. The red flag was up; fresh mail. Tucking the paintbrush into her hair and the bottle of India ink into the crook of her elbow, Beatrice flipped open the box and pulled out some utility bills, a postcard from her just-married sister in New York and a blue airmail envelope. Curious, she flipped it over.

The return address was Mosely, Birmingham, England, written in a school-marmish hand. A woman’s hand. A black cat had been drawn across the envelope flap. Underneath the tail was printed a tiny number XXVI. She’d seen that handwriting before. Years before, actually, when she’d been searching in a desk drawer for their cheque book. A stack of crisp envelopes secured with a rubber band. Underneath a studio portrait of a curly-haired blond cuddling a little dog under her chin.

Beatrice gasped. The bottle of ink tumbled down her side, leaving a wet gash of black along her flowered house dress and staining the outside of her calf. Her gaze shifted to the patch of devil’s paintbrush growing in the culvert at her feet as she sifted through her memory. That had been months after she’d refused to move the family to Liberia. She kicked the empty bottle into the ditch, raced back to the house and turned the heat on under the kettle, praying that Anthony’s correspondent had used permanent ink.

“Dearest Tony,” she read. He’d always insisted she call him Anthony. “Thank you for the pretty hankies. Mam and Sis appreciated the thoughtful gifts. I bought a lovely new blouse with the five pounds you sent. Eddie and the blokes from the pub were asking after you. The printing plant and metalworks factory are running adverts in the paper for maintenance men. They’re giving preferences to vets still, so think about that. Our Alice and I went dancing at the Palais last weekend. It’s not the same without you, though.”

Beatrice clutched her belly and sank into a chair. She couldn’t remember the last time she’d worn something lovely and new. Tears ran down her cheeks. No, she did remember. Her wedding day.

‘Forsaking all others.’ She’d never had an ‘other’ to forsake.

It was the shouts of the children in the yard that brought her out of her stupor. Leaping to her feet, she scrubbed the ink from her skin with a dishrag then grabbed a bottle of mucilage, pressed a thin line of adhesive to the letter flap and pressed it shut with the flat of her wedding band. She made a bundle of the fresh mail and some opened envelopes, crumpling it between her fingers before tossing everything down and dragging it across the tiles with the toe of her shoe. She picked the papers from the floor and organized them into a tidy pile. If Anthony asked what happened, she’d make something up. She’d dropped them in the yard and had to grab them before the wind blew everything away. But he didn’t ask.

Beatrice stopped keeping track of the numbered letters. The children were always hungry. As darkness came earlier and earlier, being housebound made them even more rambunctious. Except for the walleyed egg man and the milkman who still drove a horse and buggy, she had no visitors. The Ukrainian and Polish farmers’ wives in the vicinity had twice as many children. Even if they’d understood English, there was no time or energy for socializing. Never-ending mending. Air leaked through chinks in the walls and shovels of coal had to be fed into the furnace around the clock.

Anthony worked overtime, read three books a week and wrote poetry and letters every day. The nightmares returned; he’d escape to sleep on the couch. Conversation was infrequent, but the children’s chatter and his melancholy filled the spaces where marital congeniality had been. On New Year’s Day, she slipped carrying a pail from the indoor privy to the outhouse. He found her on the ground half an hour later, big belly-up, spattered with frozen shit, tears pooled beneath her shuttered eyes like icy commas.

Their last child was delivered in hospital, in the midst of a blizzard. Beatrice was glad for the week of enforced rest. The cards from her family and the tug of that sweet fat boy at her breast reminded her of love. She’d been faithful. The Lord would provide. She pressed the heads of the flowers her husband brought her between the pages of her Sunday Missal and got on with it.

Anthony never got around to teaching his wife to drive. It was lonely for her on the farm. That was one of the reasons he gave when, during Easter dinner two years later, he announced he was selling the farm. They were moving into an apartment above the pharmacy in town. The children balked at leaving school and friends and the freedom of roaming the countryside. Their father sent them to their rooms without dessert. Beatrice looked forward to starting afresh with hot and cold running water, flush toilets and steam heat. No more pre-teen daughter driving the tractor while Anthony wielded the sprayer of poison. No more packing fruit in frilly purple cups for hours on end, itching from the fuzz and getting stung by wasps. No more bathing last in a tin tub of lukewarm soap-scummed water.

For a time, the family rubbed along in the small apartment, lulled by town comforts like a laundromat, a public library, parks and sweets from the Italian bakery. Anthony got a second job; Beatrice joined the Catholic Women’s League, won accolades for her beautifully decorated cakes and knit socks for prisoners of war in Korea. He bought a newer used car and more books. She got a sewing machine. The ties that should have bound them frayed, but she had no experience with couple-hood and feared whatever she did or said would be wrong. He didn’t beat her or booze it up. There was no knock-down, drag-out fighting in front of the children. Even so, his tormented rage soured their smiles. Still, they’d manage.

And they did, until she discovered the dark suitcase—half-packed with his things—under their bed. He’d hung his head and paced the room like it was a cage. She wrung her hands and begged him to think of the children.

“It’s all too much,” he’d moaned, waving his arms. “The noise, the demands. I can’t take it.”

Dry-eyed, she closed the door and leaned against the jamb. “What will we do?”

“I have a bus ticket. For the day after tomorrow. Don’t worry, it will just be for a while.”

‘Until death do us part’? Their story ended with a lie, too.

Hyacinthe Miller - 1st prize, OBOA Writing Contest - 2018

Recent Posts